Bill of Rights Day: The Vision of the Founders is gone!

December 15, 2009 - Bill of Rights Day is Tuesday, December 15th. But it is not a day for celebration. Instead, it should be a day of mourning for the death of decentralized self-government.

In 2008, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled in the case of Kennedy v. Louisiana. In that decision, the Court created a new categorical right to rape a child without receiving the death penalty.

Although the majority made mention of the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition of “cruel and unusual punishment,” no one really believed that this new right had any basis in the Constitution. The Court majority claimed that its decision reflected a new societal consensus, despite the fact that six states and, as it turned out, Congress recently had adopted legislation providing capital punishment for certain child rapists. The dissenting justices said that the actual basis of the Kennedy decision was “the Court’s ‘own judgment’ regarding ‘the acceptability of the death penalty,’” but the majority opinion made clear that the Court simply differed with the people’s representatives on the question of how significant rape of a child is.

In other words, the justices substituted their legislative will for that of elected legislators. Alas, there was nothing unusual about this. Kennedy v. Louisiana illustrates what has become of the Bill of Rights in our day.

The Bill of Rights should be mourned, not celebrated. It is defunct. Intended as the bulwark of the right of decentralized self-government, it now serves mainly as an excuse for the opposite: a roving judicial veto of state policies that federal judges dislike.

So if the people of virtually every state ban flag burning or regulate abortion, provide capital punishment or support prayer in school, it does not settle the matter. Unlike 200 or even 100 years ago, today the federal judiciary is apt to step in to stop state legislatures from adopting policies like these.

The people never consented to have federal judges behave this way.

The purpose of the first ten Amendments was laid out clearly by their Preamble. “Preamble?” You might ask. “What preamble?” Although the main body of the Constitution is never published without its Preamble, one could study American history for a lifetime without ever encountering the Preamble to the Bill of Rights.

That Preamble says that Congress is recommending amendments to the states because a number of states in ratifying the Constitution “expressed a desire, in order to prevent misconstruction or abuse of its powers, that further declaratory and restrictive clauses should be added.” Since the people were afraid of the new federal government, the Bill of Rights was added to more carefully hedge in its powers.

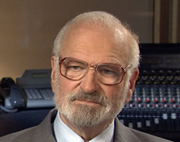

Kevin R. Constantine Gutzman is an American historian, constitutional scholar, and New York Times bestselling author of The Politically Incorrect Guide to the Constitution. He is an associate professor of the Department of History and Non-Western Cultures at Western Connecticut State University. He is an outspoken critic of excessive power of the U.S. Supreme Court. His views have been characterized as libertarian, conservative, anti-federalist and pro-states’ rights.

In 2008, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled in the case of Kennedy v. Louisiana. In that decision, the Court created a new categorical right to rape a child without receiving the death penalty.

Although the majority made mention of the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition of “cruel and unusual punishment,” no one really believed that this new right had any basis in the Constitution. The Court majority claimed that its decision reflected a new societal consensus, despite the fact that six states and, as it turned out, Congress recently had adopted legislation providing capital punishment for certain child rapists. The dissenting justices said that the actual basis of the Kennedy decision was “the Court’s ‘own judgment’ regarding ‘the acceptability of the death penalty,’” but the majority opinion made clear that the Court simply differed with the people’s representatives on the question of how significant rape of a child is.

In other words, the justices substituted their legislative will for that of elected legislators. Alas, there was nothing unusual about this. Kennedy v. Louisiana illustrates what has become of the Bill of Rights in our day.

The Bill of Rights should be mourned, not celebrated. It is defunct. Intended as the bulwark of the right of decentralized self-government, it now serves mainly as an excuse for the opposite: a roving judicial veto of state policies that federal judges dislike.

So if the people of virtually every state ban flag burning or regulate abortion, provide capital punishment or support prayer in school, it does not settle the matter. Unlike 200 or even 100 years ago, today the federal judiciary is apt to step in to stop state legislatures from adopting policies like these.

The people never consented to have federal judges behave this way.

The purpose of the first ten Amendments was laid out clearly by their Preamble. “Preamble?” You might ask. “What preamble?” Although the main body of the Constitution is never published without its Preamble, one could study American history for a lifetime without ever encountering the Preamble to the Bill of Rights.

That Preamble says that Congress is recommending amendments to the states because a number of states in ratifying the Constitution “expressed a desire, in order to prevent misconstruction or abuse of its powers, that further declaratory and restrictive clauses should be added.” Since the people were afraid of the new federal government, the Bill of Rights was added to more carefully hedge in its powers.

Kevin R. Constantine Gutzman is an American historian, constitutional scholar, and New York Times bestselling author of The Politically Incorrect Guide to the Constitution. He is an associate professor of the Department of History and Non-Western Cultures at Western Connecticut State University. He is an outspoken critic of excessive power of the U.S. Supreme Court. His views have been characterized as libertarian, conservative, anti-federalist and pro-states’ rights.