Nothing in the Constitution allows the individual mandate Obama proposes!

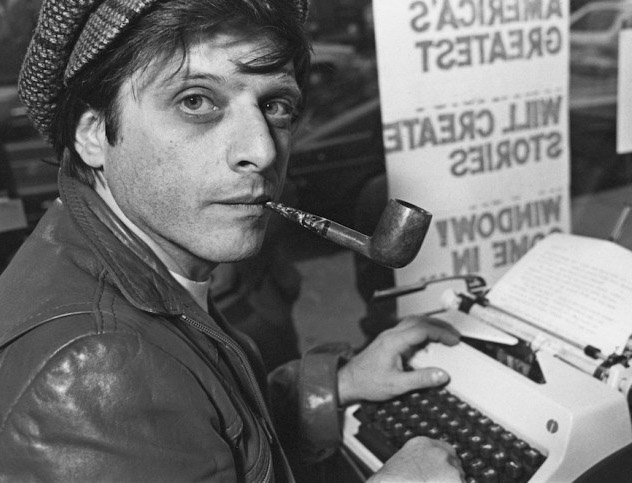

By Anthony Gregory

OAKLAND, Kalifornia - September 14, 2009 - Many liberals lambasted the Bush regime on detention policy and warrantless surveillance, often arguing that they violated the Constitution. Now the (illegitimate) Obama regime is pushing ahead with plans to require every Amerian to purchase health insurance.

Doesn't that also violate the Constitution?

The Constitution created a federal government limited to its enumerated powers. Everything Congress is allowed to do is spelled out in Article I. The 10th Amendment makes it explicit: "The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people."

Nothing in the Constitution authorizes any federal involvement in healthcare - yet Congress may soon require everyone in America to buy insurance.

Admittedly, the Supreme Court has ruled that the language empowering Congress to "regulate Commerce ... among the several States" applies to an ever-broadening range of activity. The "commerce" clause was originally intended to prohibit interstate tariffs, a supposed problem under the Articles of Confederation.

Ironically, consumers today cannot freely buy health insurance from across state lines. If there's any legitimate application of the "commerce" clause, it would be to overturn such restrictions. But the framers never gave Congress the general power to regulate industry.

In the 1935 case Schecter v. United States, involving farming regulations, the court unanimously struck down parts of the National Industrial Recovery Act for overstepping Congress's commerce power. Liberal Justice Louis Brandeis informed one of President Franklin Roosevelt's aides to "tell the president that we're not going to let this government centralize everything."

The next year, the court ruled in Butler v. United States that elements of the Agricultural Adjustment Act, which inflated food prices by restricting supply, violated the 10th Amendment.

After FDR threatened to pack the court with additional judges friendly to the New Deal, the court lost its spine. In 1937, it upheld the National Labor Relations Act - which greatly expanded the power of labor unions and greatly diminished the freedom of contract - under the "commerce" clause.

In Wickard v. Filburn (1942) the justices even upheld the conviction of a man for growing too much wheat on his farm. The court reasoned that even wheat grown solely for private consumption ultimately had an impact on the economy, turning the "commerce" clause into a regulatory rubber stamp.

The "commerce" clause is now interpreted very broadly. Although in United States v. Lopez (1995) the court struck down a firearms law that exceeded Congress's commerce power, it ruled 10 years later in Gonzales v. Raich that federal drug policy overrode California's medical marijuana laws, despite the 10th Amendment.

Justice Clarence Thomas dissented: "If the Federal Government can regulate growing a half-dozen cannabis plants for personal consumption (not because it is interstate commerce, but because it is inextricably bound up with interstate commerce), then Congress' Article I powers … have no meaningful limits." Indeed, practically nothing is beyond the pale anymore.

Then there is the privacy issue. In Griswold v. Connecticut (1965), Roe v. Wade (1973), and Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992) the court found reproductive freedom to be guaranteed as an implicit right to privacy. In Casey, the court reasoned that abortion entailed "the most intimate and personal choices a person may make in a lifetime, choices central to personal dignity and autonomy," and that such choices are "central to the liberty protected by the 14th Amendment."

Why wouldn't this apply to the right to decide whether to buy health insurance?

Other constitutional concerns emerge. The mass collection of medical data likely to occur under proposed reforms threatens the Fourth Amendment's "right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects." Making it a crime not to buy insurance, and then forcing people to show they have not bought it, arguably clashes with the Fifth Amendment's protection against self-incrimination.

The Ninth Amendment reserves to individuals all rights not expressly denied by the Constitution. Nothing in the document curtails our right not to purchase health insurance. And being forced to fill out forms to apply for insurance is in tension with the 13th Amendment's prohibition of "involuntary servitude."

The quality we could expect from government care may also raise constitutional questions. In early August, a federal panel ordered California to release 40,000 inmates because the health services were so strained, causing one unnecessary prisoner death per week, so as to render the treatment "unconstitutional." If we all become captive consumers under federal mandate, could we not similarly argue that any shoddiness in our mandated health services is an unconstitutional burden?

Those who find such constitutional arguments unconvincing are often quick to invoke them against policies they oppose. Similarly, some of today's critics of (illegitimate) President Obama and national healthcare brandish the Constitution as a holy document, but were silent when President George W.Bush trampled its many limitations on executive power, and even signed an expansion of Medicare.

A newfound, consistent, and lasting respect for the Constitution, across the ideological spectrum, would renew the health of our republic like nothing else.

Anthony Gregory is a research analyst at the Independent Institute and the author of a forthcoming book on habeas corpus.

OAKLAND, Kalifornia - September 14, 2009 - Many liberals lambasted the Bush regime on detention policy and warrantless surveillance, often arguing that they violated the Constitution. Now the (illegitimate) Obama regime is pushing ahead with plans to require every Amerian to purchase health insurance.

Doesn't that also violate the Constitution?

The Constitution created a federal government limited to its enumerated powers. Everything Congress is allowed to do is spelled out in Article I. The 10th Amendment makes it explicit: "The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people."

Nothing in the Constitution authorizes any federal involvement in healthcare - yet Congress may soon require everyone in America to buy insurance.

Admittedly, the Supreme Court has ruled that the language empowering Congress to "regulate Commerce ... among the several States" applies to an ever-broadening range of activity. The "commerce" clause was originally intended to prohibit interstate tariffs, a supposed problem under the Articles of Confederation.

Ironically, consumers today cannot freely buy health insurance from across state lines. If there's any legitimate application of the "commerce" clause, it would be to overturn such restrictions. But the framers never gave Congress the general power to regulate industry.

In the 1935 case Schecter v. United States, involving farming regulations, the court unanimously struck down parts of the National Industrial Recovery Act for overstepping Congress's commerce power. Liberal Justice Louis Brandeis informed one of President Franklin Roosevelt's aides to "tell the president that we're not going to let this government centralize everything."

The next year, the court ruled in Butler v. United States that elements of the Agricultural Adjustment Act, which inflated food prices by restricting supply, violated the 10th Amendment.

After FDR threatened to pack the court with additional judges friendly to the New Deal, the court lost its spine. In 1937, it upheld the National Labor Relations Act - which greatly expanded the power of labor unions and greatly diminished the freedom of contract - under the "commerce" clause.

In Wickard v. Filburn (1942) the justices even upheld the conviction of a man for growing too much wheat on his farm. The court reasoned that even wheat grown solely for private consumption ultimately had an impact on the economy, turning the "commerce" clause into a regulatory rubber stamp.

The "commerce" clause is now interpreted very broadly. Although in United States v. Lopez (1995) the court struck down a firearms law that exceeded Congress's commerce power, it ruled 10 years later in Gonzales v. Raich that federal drug policy overrode California's medical marijuana laws, despite the 10th Amendment.

Justice Clarence Thomas dissented: "If the Federal Government can regulate growing a half-dozen cannabis plants for personal consumption (not because it is interstate commerce, but because it is inextricably bound up with interstate commerce), then Congress' Article I powers … have no meaningful limits." Indeed, practically nothing is beyond the pale anymore.

Then there is the privacy issue. In Griswold v. Connecticut (1965), Roe v. Wade (1973), and Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992) the court found reproductive freedom to be guaranteed as an implicit right to privacy. In Casey, the court reasoned that abortion entailed "the most intimate and personal choices a person may make in a lifetime, choices central to personal dignity and autonomy," and that such choices are "central to the liberty protected by the 14th Amendment."

Why wouldn't this apply to the right to decide whether to buy health insurance?

Other constitutional concerns emerge. The mass collection of medical data likely to occur under proposed reforms threatens the Fourth Amendment's "right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects." Making it a crime not to buy insurance, and then forcing people to show they have not bought it, arguably clashes with the Fifth Amendment's protection against self-incrimination.

The Ninth Amendment reserves to individuals all rights not expressly denied by the Constitution. Nothing in the document curtails our right not to purchase health insurance. And being forced to fill out forms to apply for insurance is in tension with the 13th Amendment's prohibition of "involuntary servitude."

The quality we could expect from government care may also raise constitutional questions. In early August, a federal panel ordered California to release 40,000 inmates because the health services were so strained, causing one unnecessary prisoner death per week, so as to render the treatment "unconstitutional." If we all become captive consumers under federal mandate, could we not similarly argue that any shoddiness in our mandated health services is an unconstitutional burden?

Those who find such constitutional arguments unconvincing are often quick to invoke them against policies they oppose. Similarly, some of today's critics of (illegitimate) President Obama and national healthcare brandish the Constitution as a holy document, but were silent when President George W.Bush trampled its many limitations on executive power, and even signed an expansion of Medicare.

A newfound, consistent, and lasting respect for the Constitution, across the ideological spectrum, would renew the health of our republic like nothing else.

Anthony Gregory is a research analyst at the Independent Institute and the author of a forthcoming book on habeas corpus.