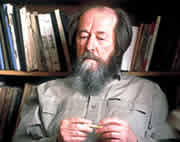

Stanislav Yevgrafovich Petrov: The Man Who Saved the World!

The date is September 1, 1983 and the Cold War between the Soviet Union and the United States is in full gear; when from the New York skies Korean Air Lines Flight 007 flies from JFK, destination Seoul, South Korea.

In the middle of the flight, while accidentally passing through Soviet air space, Soviet fighter jets appear close to the aircraft. The Soviets, who don't know the plane contains civilians, warn the pilot that they will shoot down the aircraft if it doesn't identify itself, and the pilot, for some unknown reason, doesn't respond.

Reports say the pilot never actually received the information, although theories about this are still unclear. An hour passes while the fighter jets continue to accompany the aircraft, and orders come from the Soviet military to shoot down the aircraft just as the plane is leaving Soviet airspace.

The Soviet fighter jets shoot down the plane, with the aircraft plunging 35,000 feet in less than 90 seconds, killing 269 civilians, including a U.S. congressman.

Hell breaks loose. As the Soviets try to defend their 'mistake', U.S. President Ronald Reagan describes the Soviets actions as "barbaric" and "a crime against humanity that must never be forgotten".

Tension between the two mega-powers hits an all-time high, and on September 15, 1983, the U.S. administration bans Soviet aircrafts from operating in U.S. airspace. With the political climate in dangerous territory, both the U.S. and Soviet governments are on high alert, each believing that an attack by the other is imminent.

It is a cold night at the Serpukhov-15 bunker in Moscow on September 26, 1983, as Strategic Rocket Forces lieutenant colonel Stanislav Yevgrafovich Petrov resumes his duty, monitoring the skies of the Soviet Union, after taking a shift for someone else who couldn't go to work.

Just past midnight, Petrov receives a computer report he has dreaded to see for his entire military career; the computer captures a nuclear military missile being launched from the United States, destination Moscow.

In the event of such an attack, the Soviet Union's strategy protocol is to launch an immediate all-out nuclear weapons counterattack against the United States, and immediately afterwards inform top political and military figures. From that point, any decision to further the military offensive on America will be considered by top Soviet officials.

The bunker is in full-alarm, with red lights flashing everywhere, as the missile is captured by Soviet satellites via computers. However, Petrov isn't convinced. He believes that if the U.S. did attack, they would attack all-out, not by sending just one missile and thereby giving the Soviets a chance to launch a counterattack.

Petrov figures something doesn't make sense because a single missile launched would be a strategic disaster for the U.S. He takes some time to think about the situation, and then decides not to give the order to launch a nuclear counterattack against America, since in his opinion, it could very possibly be a computer error.

But seconds later, the situation turns extremely serious; the satellite spots a second missile. The pressure exerted by the other officers in the bunker to commence responsive actions against the United States start growing. A third missile is spotted, followed by a fourth. A couple of seconds later, a fifth one is spotted... everyone in the bunker is agitated that the USSR is under nuclear missile attack.

He has two options. He could go with his instinct and dismiss the missiles as computer errors, breaking military protocol in the process, or he could follow protocol and take responsive action, commencing a full-blown nuclear war against America, potentially killing millions of people.

He decides it is a computer error, knowing deep down that if he is wrong, then missiles will be raining down in Moscow in a very few minutes.

Seconds turned to minutes, and as time passes it becomes clear that Petrov is correct; it is a computer error after all. Stanislav Petrov has prevented a worldwide nuclear war, a doomsday scenario that would have annihilated entire cities. He is a hero. His coworkers congratulate him for his superb judgment.

Upon further investigation it is found that the error resulted from a very rare sunlight alignment that the computer read as missiles.

Of course, the top brass in the Kremlin didn't find his actions to be so heroic, since he broke military protocol and if he would have been wrong, risked the lives of millions of Russians. He is sent into early retirement, with a measly $200-a-month pension, and suffers a nervous breakdown in the process.

Due to military secrecy, nobody knew of Petrov's heroic judgment until 1998, when a book written by a Russian officer who was present at the bunker revealed that World War III was much closer than most people thought, and that a nuclear holocaust was avoided by a close shave.

Petrov reminisces about what might have been if he didn't get that extra shift that night.

Even though Russian officials have little sympathy for the man who saved millions of American lives, the United Nations and a number of U.S. agencies have honored the man who could have started a nuclear war, but didn't.

In 2008, a documentary film entitled The Man who saved the World is set to be released; perhaps giving Petrov some financial help and thanking him for the incredible part he had in keeping the U.S. and the USSR out of a full-blown war.

On that cold Moscow night back in 1983, a poorly paid 44-year-old military officer saved the world and in the process made himself one of the most influential persons of the century, preserving more lives than anyone ever did, before or since.

Most of today's people don't know it, but our modern world exists because of the actions of Stanislav Yevgrafovich Petrov.

With profound humility, Petrov says he does not regard himself as a hero for what he did that day. In an interview for the documentary film, The Red Button and the Man Who Saved the World, Petrov says, " I was simply doing my job, and I was the right person at the right time, that's all. I did nothing (special)."